What Decades of Teaching Taught Me About Language, Choice, and Character

What Decades of Teaching Taught Me About Language, Choice, and Character

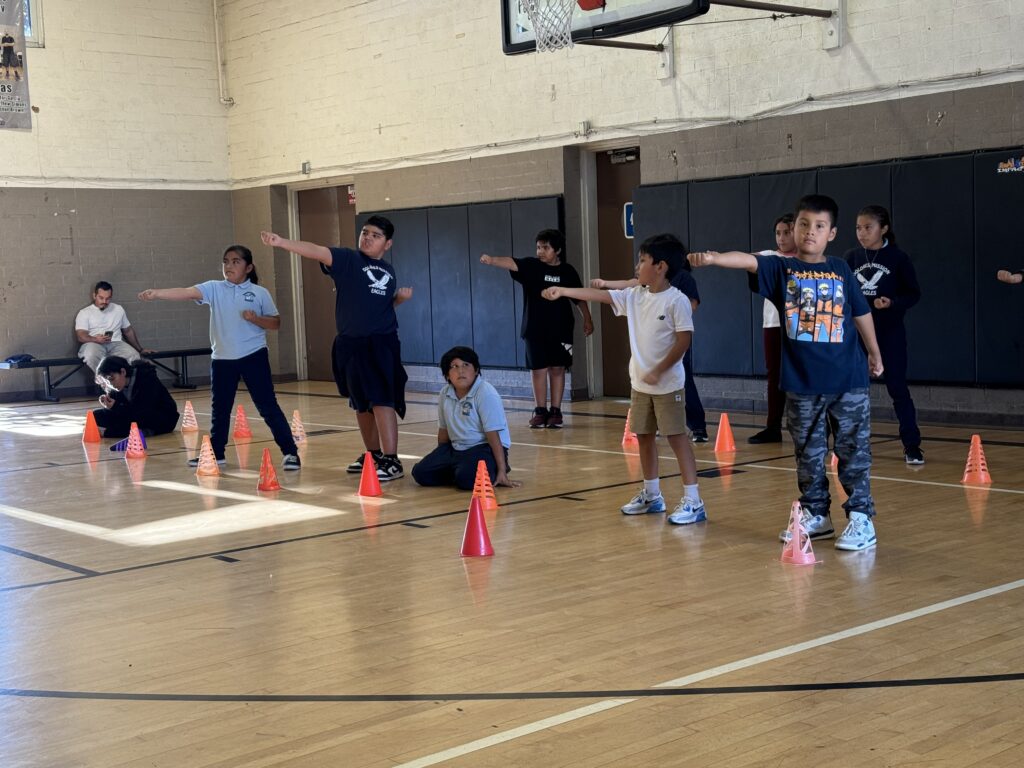

More than thirty-five years ago, when I began teaching martial arts, I quickly learned that the most important lessons had very little to do with punches, kicks, or physical technique.

Long before students struggled with form, they struggled with understanding.

These children didn’t struggle because they were unwilling to learn. They often struggled because they didn’t yet have the language to understand what was happening inside them.

As instructors, parents, and educators, we often ask children to demonstrate qualities like respect, discipline, patience, or courage. We correct behavior. We redirect actions. We explain expectations.

And yet, many children don’t fall short because they lack character—they fall short because they don’t yet understand the language behind those expectations.

In their own minds, they are not being defiant or rebellious.

They are simply in the moment.

They feel something before they can name it.

They react before they can reflect.

They act before they can recognize that a different choice even exists.

Without words, alternatives are invisible.

And when alternatives are invisible, choice is limited.

What the Dojo Taught Me About Language

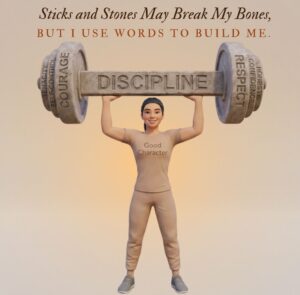

In my martial arts studios, progress was never just physical. Students didn’t advance simply by learning techniques; they advanced by learning concepts.

Words mattered.

When a student understood what balance actually meant, their stance improved.

When they understood self-control, their movements softened.

When they understood discipline—not as punishment, but as intentional effort—their behavior shifted.

Not because they were forced, but because they finally had a framework for choice.

This understanding shaped how I built my curriculum. Vocabulary was not an add-on; it was integrated into the learning process. Students were expected to understand the meaning behind the skills they practiced, not just perform them.

Over time, it became clear that character develops the same way skill does: step by step, with structure, repetition, and meaning. Before a student could demonstrate a concept, they had to understand it. And before they could understand it, they needed language.

The same principle applies far beyond the dojo.

A Lesson Learned on the Road

The seed for this work didn’t start as a teaching method or a curriculum idea.

It started much closer to home.

During long car rides with my daughter when she was young, we talked—about school, about friends, about disappointments, about wants that couldn’t be met. Like most children, she experienced emotions fully and immediately.

Sometimes she wanted something she couldn’t have—a toy, a treat, a change in plans. And like most children, she felt that disappointment deeply.

Instead of explaining or correcting in the moment, I began using a small stuffed frog and a playful voice to talk through what she was experiencing. The frog wasn’t there to teach lessons. He was there to reflect her experience—and often amplify it.

If she wanted a candy bar and couldn’t have one, Froggie wanted it too.

He would fuss.

He would complain.

He would say things like, “Other kids get candy bars—how come I can’t have one?”

By watching her feelings mirrored back in an exaggerated, humorous way, something important happened. She could see herself from the outside without being shamed. The story created space between the feeling and the reaction.

And that’s when something critical became clear.

When a word entered the conversation, everything changed.

Once she had language for what she was feeling—frustration, disappointment, fairness—she could pause. She could think. She could choose. Vocabulary didn’t control her behavior; it gave her agency over it.

Once she had language for what she was feeling—frustration, disappointment, fairness—she could pause. She could think. She could choose. Vocabulary didn’t control her behavior; it gave her agency over it.

Sometimes, she even turned the lesson back on Froggie.

She would explain to him that he couldn’t always have everything he wanted. That eating a candy bar might ruin his dinner. Froggie, after all, loved flies the way she loved fries.

In those moments, she wasn’t just calming down—she was reasoning, reflecting, and practicing choice out loud.

That realization connected directly back to everything I had seen in my teaching life.

Why “Just Behave” Doesn’t Work

Children don’t become respectful by being told to “be respectful.”

They don’t become disciplined by being told to “try harder.”

They don’t develop patience by being told to “wait.”

Those commands assume understanding that often isn’t there yet.

Children become respectful when they understand what respect is, how it shows up, how it feels to receive it from instructors and peers, and how it feels to choose it themselves. That understanding requires language.

Without words, children are trapped inside the moment. With words, they gain distance from it. And that distance is where reflection lives.

This is supported not just by experience, but by developmental research. Studies in early childhood education and psychology consistently show that expressive vocabulary and emotional regulation develop together. Children who have stronger language for describing feelings and internal states are better able to regulate behavior, reflect on choices, and engage socially.

In other words: vocabulary isn’t just academic—it’s regulatory.

The Same Pattern in the Studio

I saw this repeatedly with students in the dojo. One child struggled with frustration during drills. Another shut down when corrected. A third reacted physically when overwhelmed.

IFrom the outside, these behaviors could look like defiance or lack of discipline.

But when I slowed things down and introduced language—naming effort, explaining intention, framing mistakes as part of learning—the behavior changed.

But when I slowed things down and introduced language—naming effort, explaining intention, framing mistakes as part of learning—the behavior changed.

Not instantly.

Not magically.

But meaningfully.

Once a student could say, “I’m frustrated,” instead of acting it out, the intensity dropped. Once they understood that discipline meant continuing with effort—not being perfect—they stopped giving up. Once they had words for what they were experiencing, they could participate in their own growth.

That’s when I realized something fundamental:

Language creates the conditions for choice.

Why Story Matters So Much

Vocabulary taught in isolation has limited impact. Children can memorize definitions and still struggle to apply them. What gives words power is context.

Stories provide that context.

Stories allow children to observe choices without being judged. They let kids see mistakes without shame. They provide a mirror instead of a command. And when vocabulary is introduced through story—especially when a character gets it wrong in a big, funny, human way—it stops being a definition and starts becoming a usable tool.

Through story, children can explore questions safely:

- What happens when I lose my temper?

- What does responsibility look like here?

- How does respect feel when I give it—or don’t?

The character becomes a proxy for reflection.

The word becomes a lens.

Vocabulary as Agency

The goal of this approach has never been to create perfect behavior.

Perfection shuts learning down.

And it’s easy to let perfect get in the way of better.

The goal has always been to give children words they can use to navigate their inner world.

Because when children have language, they gain agency.

When they gain agency, they gain confidence.

And when they gain confidence, they begin to grow—on purpose.

This is as true in a martial arts studio as it is in a classroom or a living room.

Children don’t need fewer feelings.

They need more words.

They don’t need to be controlled.

They need to be equipped.

Why Vocabulary Comes First

Vocabulary comes first because it creates choice.

Choice creates agency.

Agency creates growth.

That is what decades of teaching have shown me—on the mat, on the road, and in everyday moments with children trying to make sense of their world.

And that is why language isn’t a side note in character development.

It’s the starting point.

If you’d like to read more about how the little frog helps to teach kids about vocabulary, watch for the “Adventure of Froggie Beenwell”, a book series coming out in 2026