Throughout life, we learn that the world is navigated through a complex intersection of sensory experiences. From the vibrant hues of a sunrise that we observe with our eyes to the delicate aroma of freshly brewed coffee that we sense through smell, our senses shape how we interact and perceive the environment.

Throughout life, we learn that the world is navigated through a complex intersection of sensory experiences. From the vibrant hues of a sunrise that we observe with our eyes to the delicate aroma of freshly brewed coffee that we sense through smell, our senses shape how we interact and perceive the environment.

While many are familiar with the classic five senses—sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch—recent scientific research has shed light on the existence of three additional senses, expanding the understanding of sensory perception.

These three senses (proprioception, vestibular sense, and interoception) also play an integral part in the unique experiences we have and partner intricately with the traditional senses we have all known. While we may be less familiar with how they affect us daily, they are no less vital to the complex concept of how we perceive and experience things differently.

Diving into how sensory integration shapes our perception of the world and its implications for all individuals, especially those with neurodivergent conditions, is a subject worthy of dissection. By understanding the intricacies of sensory processing, new possibilities arise for personal growth, learning, and comprehensive well-being.

The Traditional Five Senses and Neurodivergence

Whether it’s something as simple as watching your favorite football game or having a picnic in the park, we all have varying preferences when it comes to our senses. Some might prefer quieter venues while others thrive off continuous action. Others might prefer spicy foods, and some cannot tolerate anything more than black pepper. So, why are we so drastically varied when it comes to our perception of our environment?

Without going too deeply into the vast expanse of research within the field of neuroscience, a widely accepted concept regarding how we interpret sensory information and process it is known as “conceptual association”. Essentially, conceptual association refers to our tendency to link specific emotions and expectations with the way our senses respond to stimuli. Once we’ve had an initial experience, our brains become conditioned to anticipate that the same sensation will be repeated when we encounter that item/event again. When these expectations aren’t met and something deviates from the norm, it can significantly disrupt our perception (Rago, 2014).

Because we all experience things differently and at distinct stages of our lives, these perceptions will vary. Of course, this concept is overly broad based, but the idea is the same – everything that we experience through our senses results in an emotion and expectation that is stored in our brain for future encounters.

However, the idea of conceptual association in the world of neurodiversity takes on a much more extreme definition. As many individuals on the autism spectrum, for example, experience their senses in either an under-responsive or over-heightened state, sensory perception can take on a much more dramatic role (Marco, Hinkley, Hill, & and Nagarajan, 2012).

“…one might conjecture that if the auditory input (for example) is perceived as unpleasant or noxious, (those on the spectrum) will learn to avoid such auditory input, and thus curtail the learning that comes from listening to the people and world around them” (Marco, Hinkley, Hill, & Nagarajan, 2012).

This action of avoidance has obvious implications in the realms of education and skill development and in day-to-day life for neurodivergent individuals. Opportunities to fully experience events and sensations become laden with fear and avoidance rather than excitement and anticipation.

This action of avoidance has obvious implications in the realms of education and skill development and in day-to-day life for neurodivergent individuals. Opportunities to fully experience events and sensations become laden with fear and avoidance rather than excitement and anticipation.

Sensory overload instances that lead to avoidance can completely overwhelm someone who is on the spectrum, for example, and cause frustration, anxiety, and anger (Neff, 2024). These emotions can quickly turn into self-doubt and create a fear-based environment where an individual feels as if they cannot function (Neff, 2024).

While this is just an overview of the negative effects of sensory overload and negative conceptual associations, it’s important to dive deeper into how the senses coincide with one another, how that interplay affects neurodivergent individuals, and what the addition of these three “new” senses really means in the bigger picture.

The Three “New” Senses and Neurodivergence

We know that our senses don’t always independently operate – that is, our perception is often based upon more than one sense creating the conceptual association that accompanies our emotions and expectations.

When we smell something that we enjoy eating, for example, we not only associate the scent of the item, but chances are, we remember how it tasted the last time we ate it – we can feel it in our mouth, and perhaps even remember the environment we were in when we last had it. It’s not simply about the scent, but rather the whole experience.

The three additional senses – proprioception, vestibular, and interoception – are deeply intertwined within this connected experience of our perception. If you aren’t already familiar with what they mean, here’s a short synopsis:

– Proprioception: proprioception provides us with awareness of our body’s position and movement in space, facilitating activities such as walking, running, and fine motor skills.

– Vestibular: vestibular is about maintaining balance, spatial orientation, and coordination, and how it helps us adapt to changes in movement and gravitational forces.

– Interoception: interoception allows us to perceive internal bodily sensations such as hunger, thirst, temperature, and pain, and how these perceptions influence emotional awareness and self-regulation.

Drawing from the same example of enjoying a meal, we can observe how proprioception aids in the physical act of eating, ensuring that you can bring food to your mouth without spilling it. If, for instance, you drop something, the vestibular sense comes into play to help maintain balance. Additionally, interoception plays a crucial role by signaling feelings of hunger to initiate the eating process. This intricate interplay among the senses can present significant challenges in the realm of neurodivergence.

We know that sensory overload can completely halt an individual – neurotypical or neurodivergent. However, because many neurodivergent people either experience the hypersensitivity or hyposensitivity we covered earlier, they may reach that overload phase much quicker and much more severe than someone who is considered neurotypical. Because our senses often intertwine, this process can be incredibly difficult and overwhelming for those on the spectrum.

“…when we are overwhelmed by sensory input, our nervous system goes into a state of hyper or hypo arousal, which activates the fight-flight-or-freeze response. This can lead to feelings of panic, agitation, and a sense of being out of control. Additionally, when the brain receives too much information from the senses, focusing, concentrating, and making decisions can be challenging. This can exacerbate feelings of confusion, anxiety, and frustration” (Neff, 2024).

Understanding the profound impact of sensory overload, particularly for neurodivergent individuals, lays the groundwork for exploring strategies to navigate the sensory world with greater ease and resilience. Because sensory interplay is such a large part of our perception, it is evident that managing sensory input effectively is essential for promoting well-being and minimizing overwhelm.

Navigating the Sensory World

While it may seem complicated, there are several different practical approaches that we can utilize to navigate the sensory landscape and create a more harmonious relationship with our senses.

While it may seem complicated, there are several different practical approaches that we can utilize to navigate the sensory landscape and create a more harmonious relationship with our senses.

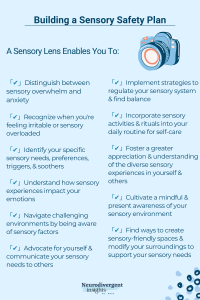

Dr. Neff, a late-in-life diagnosed Autistic-ADHD Psychologist, advises individuals to first create a Sensory Safety Plan (SSP). An SSP, as shown in the graphic, is a way to view your hypo/hypersensitivities to sensory experiences and allows you to view these sensitivities in an objective and positive light. Whether your personal plan includes avoiding these sensory triggers or learning to deal with them, a SSP is an effective way to navigate the topic of sensory overload.

“Disconnection from our bodies or the perpetual act of masking our true selves can obscure our awareness of our authentic sensory preferences and needs.

In such circumstances, investing time and effort into unraveling and embracing our unique sensory landscape becomes even more vital. By dedicating ourselves to this process of self-discovery, we lay the groundwork for a robust and effective sensory safety plan. This exploration of self-awareness marks the gateway to a world where our sensory needs are acknowledged, understood, and accommodated, setting the stage for greater sensory regulation and sensory safety” (Neff, 2024)

After identifying your individual needs and triggers, it’s crucial to establish a contingency plan. This involves preparing for situations where it may not be possible to avoid sensory overload triggers, and instead focusing on strategies to effectively manage and cope with them.

Dr. Neff (2024) recommends engaging those around you in conversation about potential sensory overload situations and journaling your triggers/overload experiences. This helps to put each occurrence into perspective and identify environments that may not be conducive to growth and comfort. From here, it’s easier to avoid scenarios that may be upsetting (if possible) or to prepare for them by doing the following:

- Use noise cancelling headphones if you know you’re predisposed to auditory sensory overload.

- Wear dark colored glasses if you know that bright lights can be irritating.

- Identify a “safe space” in your environment that is quiet and calming where you can retreat to if needed.

Of course, this list is not exhaustive but rather a starting point to identify how/when you can avoid sensory overload.

Finally, create a sensory kit. A sensory kit can include any number of things that you know will combat overload and anxiety and keep it with you when you are out. Knowing that you have things close to you that will help you relax will sometimes be enough to divert your brain away from panic and anxiety (Neff, 2024).

Finally, create a sensory kit. A sensory kit can include any number of things that you know will combat overload and anxiety and keep it with you when you are out. Knowing that you have things close to you that will help you relax will sometimes be enough to divert your brain away from panic and anxiety (Neff, 2024).

By equipping ourselves with the tools and resources needed to manage sensory challenges effectively, we empower ourselves to lead more fulfilling and balanced lives. Whether it’s preparing for a sensory overload scenario or learning our triggers to avoid them completely, we can often play a part in our own navigation of the world of sensory perception.

We can easily see that it is vital to foster a greater understanding and support for individuals with diverse sensory needs. Because our senses are so intertwined, we must not only understand how they work but how they can positively and negatively affect our existence.

By acknowledging our triggers, preparing “just in case,” and having meaningful conversations with those we encounter daily, we can play an active role in mitigating our anxiety and potential stress by reducing or even eliminating potential sensory overload scenarios.

References

Marco EJ, Hinkley LB, Hill SS, Nagarajan SS. Sensory processing in autism: a review of neurophysiologic findings. Pediatric Res. 2011 May;69(5 Pt 2):48R-54R. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182130c54. PMID: 21289533; PMCID: PMC3086654.

Neff, M. A. (2024). Understanding Sensory Overload and its Impact on Emotions. Neurodivergent Insights. Retrieved from https://neurodivergentinsights.com/blog/sensory-overload-and-emotions#:~

Rago, R. (2014). Emotion and Our Senses. Emotion, Brain, and Behavior Laboratory. Retrieved from https://sites.tufts.edu/emotiononthebrain/2014/10/09/emotion-and-our-senses/

*All graphics courtesy of Dr. M.A. Neff (2024)*